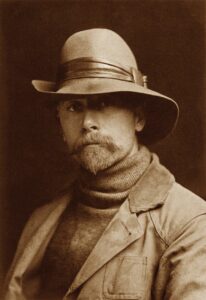

Edward Curtis was the uneducated son of a wild-eyed revivalist preacher from the late 19th century. As Edward grew into his manhood, he migrated west to Seattle. He discovered two great loves, followed later by a third. The first was mountain climbing, the second was photography, and the third the North American Indian. A serendipitous encounter somewhere on the side of Mount Reinier forever altered the course of Edward Curtis’ life. He heard the calls for help, packed up his photography equipment, and investigated. He discovered a wholly lost party of mountaineers, among whom was Geroge Bird Grinnell, Ph.D. from Yale, founder of the Audobon Society and editor of Forest and Stream — also the worlds leading expert on plains Indians at the time; and C Hart Merriam, the co-founder of the National Geographic Society. This chance encounter and subsequent rescue put Edward into the stratosphere of influential and powerful people, especially when they discovered his talents as a photographer. He was recruited for a high-profile expedition north with a team that was a veritable “who’s who” of wealthy Americans and academic elites. These connections and the quality of Curtis’ work would one day open the door for him to become the personal photographer of Theodore Roosevelt, the 26th president of the United States (1901-1909). All this was but a footnote compared to the real passion of Edward Curtis’ life.

He discovered two great loves, followed later by a third. The first was mountain climbing, the second was photography, and the third the North American Indian. A serendipitous encounter somewhere on the side of Mount Reinier forever altered the course of Edward Curtis’ life. He heard the calls for help, packed up his photography equipment, and investigated. He discovered a wholly lost party of mountaineers, among whom was Geroge Bird Grinnell, Ph.D. from Yale, founder of the Audobon Society and editor of Forest and Stream — also the worlds leading expert on plains Indians at the time; and C Hart Merriam, the co-founder of the National Geographic Society. This chance encounter and subsequent rescue put Edward into the stratosphere of influential and powerful people, especially when they discovered his talents as a photographer. He was recruited for a high-profile expedition north with a team that was a veritable “who’s who” of wealthy Americans and academic elites. These connections and the quality of Curtis’ work would one day open the door for him to become the personal photographer of Theodore Roosevelt, the 26th president of the United States (1901-1909). All this was but a footnote compared to the real passion of Edward Curtis’ life.

As Curtis mingled with elites, he became aware of a heartbreaking tragedy. Entire civilizations were being systematically wiped out by stringent government policies that forced an assimilate-or-die mandate. The culture, languages, religions, and very existence of hundreds of unique people groups were being lost to history, and it was all on purpose, all by design! Curtis could not stomach the loss. Over the next 30 years, he embarked on an epic journey to preserve the cultures of as many North American Indian tribes as possible. He did so without government support and at significant personal risk and cost. In the end, Curits produced 20 volumes masterfully preserving languages, songs, religious practices, and cultural identifiers of dozens and dozens of tribes from the Hopi in the south to the Inuit north of the Artic circle. To preserve the vanishing ways of the Indians visually, Curtis took over 40,000 photographs and produced a movie. Curtis’ all-consuming passion for adding flame to the flickering candles of dying civilizations succeeded. His work kept the candle burning, and his books and photographs have provided the sparks necessary to reignite a forest fire of interest and respect for indigenous ways in Western society.

Sadly, Curtis, though wildly famous for a time, died a penniless, divorced, broken, and largely forgotten man. His herculean efforts, without proper funding, bankrupted him. His 17-hour work days and months away from home soured his marriage. The bitter divorce that followed even landed Curtis in jail for a short time, but such was the cost of this man’s passion. Curtis had the benefit of a single focus for his entire life. He is a hero in a righteous cause, but as history teaches us over and over, greatness requires sacrifice.

Quotes and thoughts from the book:

- Cut your hair or go to jail: Curtis quickly picked up on the Hopis’ low regard for white people. They resented missionaries, who constantly told the Indians that everything they believed was sanctified garbage. They despised government authorities two thousand miles away in Washington, who ordered the men to cut their hair or face fines and imprisonment. (53)

- Decimated: 1497 — the Estimated population of indigenous peoples in North America: 10 Million. 1900 — US census recorded 237,000 indigenous people remaining. (56)

- A side note on Roosevelt’s daughter: “Princess Alice,” her family

nickname, was a heartthrob for men of many ages, a high-spirited beauty. “I can be president of the United States, or I can control Alice,” said Roosevelt. “I cannot possibly do both.” (85)

nickname, was a heartthrob for men of many ages, a high-spirited beauty. “I can be president of the United States, or I can control Alice,” said Roosevelt. “I cannot possibly do both.” (85) - Before Roosevelt came to respect Indians, he said of them terrible things: “I don’t go so far as to think that the only good Indians are dead Indians, but I believe nine out of every ten are, and I shouldn’t inquire too closely into the case of the tenth.” (88)

- Freedom of Religion for all, except the Indian: The tribe was under siege by government agents, who had jailed some of the medicine men for practicing their rituals. Freedom of religion was cherished as a sacrosanct American right — everywhere, that is, but on the archipelago of Indian life.

- It wasn’t all peace and serenity before the white man came: The Crow feared the Sioux more than they did the whites. If captured by a Lakota, a Crow knew he would be facing mutilation, burning, eye-gouging and other forms of slow torture. So when Custer and his bluecoats arrived with cannons and rapid-firing guns, the Crow saw a chance for a permanent advantage in the northern plains. (152)

- Heartbreaking abuse: As he gathered oral histories, Curtis could not contain his disgust at the epic of torture these natives had endured — starved, sickened, raped, betrayed, run-down, humiliated. “The principal outdoor sport of the settlers during the 1850s and 60s seemingly was killing Indians. There is nothing else in the history of the United States which approaches the inhuman and brutal treatment of the California tribes. Men desiring women merely went to the village or camp, killed the men and took such women as they desired. (260-261)

- Not a fan of Missionaries. In Curtis’ view, these agents of authority should occupy a special place in hell alongside missionaries. (268) On the Island of Nunivik, Curtis remarked, “At last, and for the first time in all my thirty years work with the natives, I have found a place where no missionary has worked. Should any misguided missionary start for this island, I trust the sea will do its duty.” Later on that same trip, Curtis recorded in his journal. “Moved upstream three miles to be near an old informant. This man has been driven from the village by the missionaries owing to his refusal to be a Christian. The old man is a cripple and a most pathetic case. Missionary will not allow relatives to assist him in any way. (286) I want to believe that Christian missionaries did more good than harm, but it’s much harder to draw this conclusion after reading this book.

- Drugs and Worship. In defence of the native use of hallucinatory drugs to enhance their worship experience Quannah Parker the last chief of the Comanche, argued, “The white man goes into his church and talks about Jesus, but the Indian goes into his tipi and talks to Jesus.