- She should have died, but she didn’t

- The brutal cruelties of her life should have filled her with unquenchable rage, but they didn’t

- The unfathomable loss that came with her situation should have overcome her with suicidal depression, but it didn’t.

- The bleak darkness that snatched away her youth should have turned her into a bitter and jaded woman, but it didn’t

- Over seven decades of PTSD, packed with survivor’s guilt and self-blame should have at so many points along the way utterly ruined this remarkable woman’s life.

But it didn’t

Why?

Because, as Edi says fifty times or more in her book

“No one can take out what you put in your mind.”

Life will rob you of everything; suffering is universal, but how I process that suffering, how I grieve it, how I release myself from the guilt that surrounds my trauma is up to me.

It’s my choice.

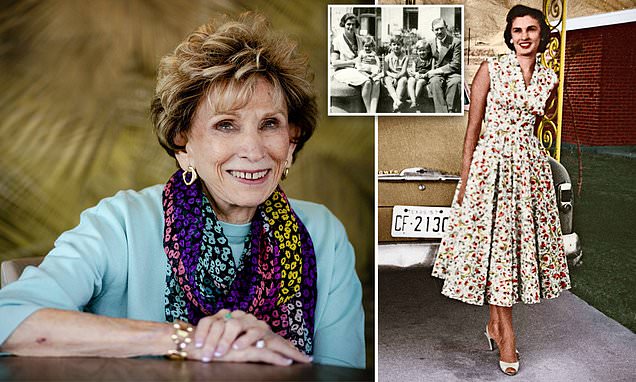

Hungarian Jew, Edith Eger was a promising dancer and gymnast with Olympic aspirations.

At the tender age of sixteen, she had tasted the joys of young love, but then the Nazis came and snatched it all away. Edith’s family was rousted out of their home in the middle of the night and warehoused in the squalor of an abandoned brick factory. They were then jammed into cattle cars and shipped to Auschwitz. Upon arrival, the band was playing happy music; the sign above the gate said,

“Those that work shall be free.” “See,” Edi’s dad said, “It won’t be so bad.”

The soft-spoken, almost kind seeming Dr. Josef Mengele met them as they stumbled forward. This black-hearted SS Doctor welcomed his job of determining who lived and died at Auschwitz. If the Doctor thought you were under 14 or over 40, he sent you left to the gas chamber; if the flick of his finger pointed you to the right, you remained alive for the time being. Of course, no one coming off the trains knew this. He looked Edi in the eyes.

“Excuse me, is this your mother?”

Edi answers truthfully. Mengele motions her mother to the left and she to the right.

“Don’t worry,” Mengele says with a reassuring smile, ‘you’ll join your mother soon.”

Mengele’s twisted mind appreciates Edi’s physical qualities. The murderer of her mother, father, and boyfriend forces her to dance for him. He wants more. He comes close, but the duties of mass murder call him away at the last second.

The Germans are losing the war, but still, they don’t want to give up their slaves. Back into the cattle cars, the survivors go, back to Germany. They work round the clock in the factories of the German war machine until the allies bomb them out. They are placed atop Nazi supply trains as human shields until the trains are destroyed from the bombs that fall from the sky. They are forced to march for days on end to arrive at still more concentration camps. If you falter even for a second, the guards snuff out your miserable life with a bullet or a bayonet.

Edi can’t go on; she stumbles, but hands reach down and pull her up. Her sister and her friend will not let her die. In Auschwitz, when she danced for Mengele, he had given her a loaf of bread. She shared it. That kindness is not forgotten in her moment of weakness now. On the same march, in a bombed-out hut, they lay down. This time Magda, Edi’s sister, cannot go on. Edi must do something. In foolish defiance of the guards, she sneaks out of the hut, climbs a fence, and pulls a few carrots from a forbidden garden. As she returns, a guard points a gun at her chest. The stolen carrots will cost her life but inexplicably he lets her go. She hears him lie to the other guards that she had been relieving herself. The following day brings another selection line.

“You who stole the carrots come forward!”

Edi sees clearly now; her execution is to be public. She is to be made an example. Instead, that same guard says to her

“You must be really hungry to attempt something so foolish” He drops a loaf of bread beside her on the floor and walks out.

The war ends, but so also Edi’s life. She finds herself in a pile of corpses at the far end of the camp. American GI’s stumble around in shock, many vomit.

“Is anyone alive?” they call out, towards the piles and piles of bodies.

Edi is too weak to talk. Finally, someone notices her. She is not quite dead. M&M’s are slipped into her mouth, she is too weak to chew, but she is saved.

A few weeks later, a drunken G.I. almost rapes her. He is mortified by his indiscretion and spends the next six weeks nursing her back to life. Back in Hungary, Edi tries to process the losses. Of the 15,000 Jews in her hometown, only 70 remain alive.

She enters into a marriage of convenience. Bela has food so she will marry him. Then Communism comes. There is more persecution and more anti-semitism. She rescues her husband from prison by bribing the guard and together they make a daring escape to America.

In their new country poverty and PTSD crumble their marriage, Miraculously after two years, Edi’s ex-husband wins her back and there is a slow journey of healing. Help comes from Viktor Frankl. Edi is inspired to continue her education, She finds her voice through her vocation. As a clinical psychologist, she becomes an expert at helping people free themselves from the prison of their own trauma.

35 years after liberation from her German oppressors an invitation comes to speak to U.S. military personnel in Germany at the former Nazi HQ in the Bavarian mountains. In the very place that planned out her death, she is now commissioned to share her story of life. Even still, survivors’ guilt, self-doubt, and deadening flashbacks make this journey almost impossible for her but she perseveres. Edi even extends her stay and completes her time in Europe with a visit to Auschwitz.

Throughout Edi’s long life she has come to see over and over that flourishing in spite of suffering comes only when we fill our minds with the right beliefs about ourselves and others, and make choices based on those beliefs.

In her own life, she chooses to forgive herself for her mother’s death. She chooses to forgive Hitler and Mengele. Granted, she agrees with her sister’s short commentary, “Hitler really fucked us up!” But through forgiveness, she lets go of these evil people’s control of her. She will move on. She will not ask “why me” Instead she asks “what now?” She will grieve the losses properly and be grateful for the gains. She will reject a life of victimhood, take responsibility, and use her experience and her abilities to bring goodness back into the world.

Quote-worthy

-

Suffering is universal, but victimhood is optional.

-

The better question for a survivor is not “why me” but “what now”.

-

Reframing and reforming damaging beliefs is the key to change. Belief is at the core of all of us.

-

Self-acceptance is the hardest part of healing.

-

To be free is to live in the present.

-

Doing what is right is rarely the same as doing what is safe.

-

There is no forgiveness without rage