My head is down. I’m frantically scratching something in my journal. I’ve had a good thought; desperately, I try to get it down before it leaves my mind—words on paper it’s a compulsion for me. So I do it religiously every morning, on a bench, on the seawall, in Vancouver. But this morning, someone has noticed my morning ritual. She’s intrigued. Who is this person that writes like his life depends on it?

Finally, her curiosity gets the best of her. So she comes a little closer.

“Hi,” She says with a smile.

“Good morning,” I say, popping my head up.

“Are you a writer?”

“Sure am, I have a day job too, but writing is my favourite thing.”

“Me too! She exclaims.

As we talk, she tells me about the book she has written,

“Sounds interesting,” I say as I celebrate the accomplishment with her.

Quickly she says, “next time I see you, I’ll bring you a copy.”

“Well, If you do that, I will definitely read it and even review it if you like.”

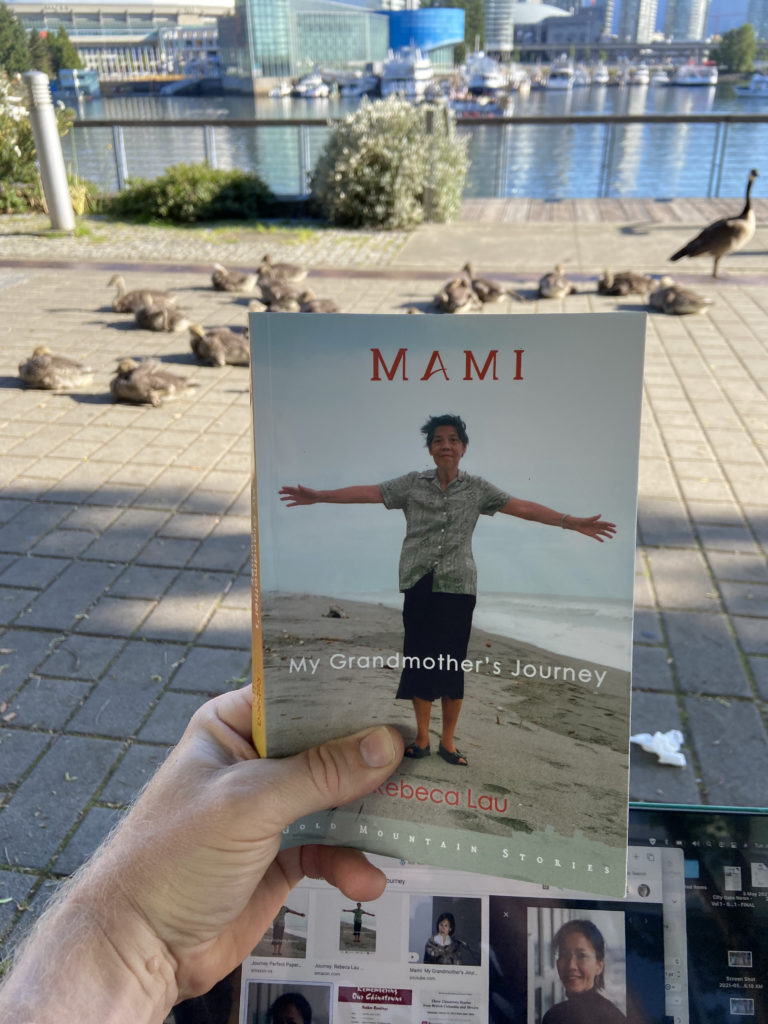

A week or so later, she spies me on a bench and gives me her book.

Great job, Rebecca, your book is lovely. I’m happy to have read it and glad to have met you. Hope to see you on the seawall again soon. What was so important to Rebecca that caused her to put together a 225-page book? — Her grandmother.

Mami was born in China sometime in the 1920s. In China, at that time, marriages were arranged, so she met her husband Teti on her wedding day! This is a most difficult concept to appreciate for a Western mind sold on romance as the key to lasting love. But for these two, the match worked.

Teti had left China for Mexico to seek his fortune. He came back to China for marriage but couldn’t stay too long. Soon he was on a boat back to Mexico, preparing the way to bring his bride over. He left Mami pregnant with the promise to bring her over as soon as possible. But then the war hit. Mami and her baby Papito (Rebecca’s dad) were forced to flee. They bounced around China only a step away from starvation or capture for many years.

The war years were brutally stressful. Once when fleeing the Japanese in a boat, Papito was crying too much. The others fearing capture urged Mami to throw the screaming child overboard. Another time when food was scarce, fellow refugees tried to persuade Mama to sell her son. These were hard choices for hard times, but Mami refused all situations that might separate her from her boy.

Finally, after a decade of chaos, the family was reunited. Even still, getting into Mexico was tricky. There wasn’t a legal means to do it, and the forgery had a picture of a woman much younger than Mama on it. So there was a lot of concern to which the artist who created the phoney paperwork said

“All Chinese look the same to most Mexicans, so there is nothing to worry about” Evidently, he was right; Mami got in no problem.

The book wanders through Chinese life in Mexico. As the story unfolds, we learn of the expanding family business, the multiplication of children and grandchildren. Then, the tragic loss of life, uncovering infidelity during the war years, the remembrances of everyday life as a shopkeeper’s granddaughter, beach trips, Mexican Chinese relationships, and food. The work is a veritable recipe book for Chinese Mexican cuisine.

There is one issue in this book that is harder for me to grasp than even arranged marriages. Teti believed so strongly that his children needed to be raised as Chinese that he sent them all back to China as young children! Mami had no say in the matter. Her duty was to get on a plane to Hong Kong, drop her kids off with relatives and then fly back to Mexico without them. As a result, her children were out of her care for approximately ten years. It would seem in Teti’s mind that being raised exclusively in Chinese culture was more important than the benefits of being raised in one’s own family. This is unconscionable to me.

I have four kids, and outside of fear for their safety on account of war, I can’t think of a single reason why I would ever send them away. In addition to this book, I’m reading a book about Japanese immigration in Canada, and I’m discovering the same thing. Children of immigrants being sent back to the homeland to be raised with the proper language and culture. I felt the despair of Mami in the book. She had endured so much separation during the war years, and now her family is finally together in Mexico only to have to send her kids all away. I would not have been able to do it. While culture is significant, it seems like a misplaced priority. Perhaps if I ever see Rebecca again I’ll ask her to help me understand the thinking.

I have a Grandpa who is 101, he has a truckload of stories about growing up on the prairie’s during the Great Depression, certainly enough to fill up the pages of a book. Rebecca you might have just inspired me to write a book!

If you would like to know more about the book, or purchase you own copy, do it! You can discover everything you need at Rebecca’s website: http://www.rebecalau.com

2 Responses

❤️

I cannot imagine sending our children away. This is a lovely review of this incredible story. The strength of the human spirit amazes me!