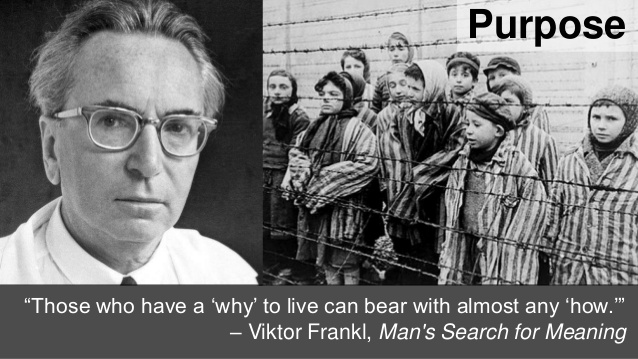

Victor Frankl was no stranger to pain suffering and death, even before the war as a successful neuroscientist and psychologist in Vienna, his practice led him to spend the majority of his time with suicide patients. In his research among these troubled souls, he found that 100% of them could not answer the question “Why am I here?” The absence of any ultimate meaning in his patient’s lives was the common thread in their suicidal perspective. Further, he discovered that alcoholism, drug abuse, and most forms of neurotic behaviour were connected to the absence of meaning in a person’s life.

As his research broadened he was startled to find that as much as 78% of German/Austrian young people in the mid 1930’s would rather have a clear transcendent meaning to their life than just making lots of money, or living for themselves. Sadly, Hitler capitalized on this “existential vacuum” as Frankl liked to called it. According to Hitler there was a transcendent reason to live and die. He was the Saviour to follow and the Third Reich was the heaven to build, and brutality was the necessary equipment needed for the project. This was better than the boredom and despair that a meaningless existence was bringing to the youth of the nation of Germany.

The Nazi’s took over Vienna. Victor was Jewish, so that was a problem. First he faced the indignity of being terminated from his post at the university and hospital. Second, he and his wife suffered through the forced abortion of their pre-born child. Third, his grief was multiplied when he witnessed the arrest and deportation of all of his extended family members, including his elderly parents, his bereaved wife, and his brother. Finally, his own arrest and internment at Auschwitz, the most notorious of the extermination camps came. By the time it was all over he was the lone survivor among all his family and friends who went to the camps.

His discoveries at the extermination camps agreed with his earlier findings on the importance of transcendent meaning being critical to the health of a person’s life. The prisoners that survived clung to some meaning, some reason to carry on — those who were not able to grasp any kind of meaning to the madness of their existence simply gave up and died off.

Of course, even those who had a greater purpose to their life died with ridiculous efficiency as well. Greater purpose did not mean you would survive, in many cases living by transcendent scruples just got you killed quicker, but somehow even the deaths of these meaning-filled creatures were different. Frankl observed:

“They marched upright into the gas chamber with the Lords prayer or kaddish on their lips, offering whatever help they could to others.”

Their grasp of a “super meaning” as Frankl liked to call it gave them a confidence that there was meaning in suffering and meaning even in death itself. This confidence, allowed them to cope, to be at peace even as their lives were taken from them in the most despicable of ways.

The whole point of the camp was to dehumanize, to turn people into animals, it worked for many, but those who could hang onto meaning retained their humanity.

When Frankl was liberated it took him just 9 days to write the book for which he is most famous. “Mans Search for Meaning” has sold 10’s of millions of copies world wide, and has been translated into some 40 different languages. Is Frankl on to something when he says we need a “super meaning” beyond ourselves to truly flourish a human beings?

Yes.

He gives several suggestions for how we as humans might be able to find greater meaning to our lives:

- Finding meaning through a life’s work — Frankl stayed purposed during his time in camp, by secretly re-writing on tiny scraps of paper the manuscript for his book that the Nazis destroyed with his entry into the camp.

- Finding meaning through deeds — Frankl turned down an opportunity (albeit a risky one) to escape in order to stay with some of the sick in the camp that he had been charged to care for, it was the right deed to do.

- Meaning through love — For Frankl the ultimate purpose for existence is love. In his own case, as he suffered, there were moments in the midst of it all, where his mind was transported to Tilly his wife. She spoke to him in his distress, and he dreamed of better days with her. He carried on, for her.

This is why things were even more difficult for him when he finally got out and discovered that she and everyone else he loved were dead.

“The best have not returned (also, my best friend [Hubert Gsur] was beheaded) and they have left me alone. In the camp, we believed that we had reached the lowest point—and then, when we returned, we saw that nothing has survived, that that which had kept us standing has been destroyed, that at the same time as we were becoming human again it was possible to fall deeper, into an even more boundless suffering. There remains perhaps nothing more to do than cry a little and browse a little through the Psalms.”

Frankl says ultimate meaning makes you human (animals don’t probe the depths of their own suffering) we do. Somehow that meaning becomes fullest when it’s connected to true love. The best reason for living, for suffering, for overcoming, and even for dying is love.

As a follower of Jesus this book, though entirely secular in nature, made me appreciate with renewed clarity the grand story of Jesus that I have come to love. The Christian story fits perfectly with Frankl’s findings. Love forms in us our greatest meaning which makes us truly human. To love, however, has its risks, for when that love dies or is somehow extinguished, we become susceptible to great despair. However, if our love is attached to a person who even death cannot vanquish, how then can despair conquer us? it cannot!

2 Responses

This is wonderful, Dennis. Every sentence of it. I learned so much. The only thing I might quibble with a bit is your one assessment in the final paragraph of the book as “secular.” It seems to me deeply sacred and rooted in Frankl’s Jewish faith/praxis. But that final glorious announcement of a love attached to one whom death was not able to vanquish… oh, that is such good, good news.